«Більше поезії. Танцюй» Поезія і переклад

Дода_ла: pole_55 03 Листопада 2016 о 11:16 | Категорія: «Статті» | Перегляди: 5821

Матеріал підготува_ла: Тетяна Манзюк | Зображення: з архівів Творчої аґенції «АртПоле»

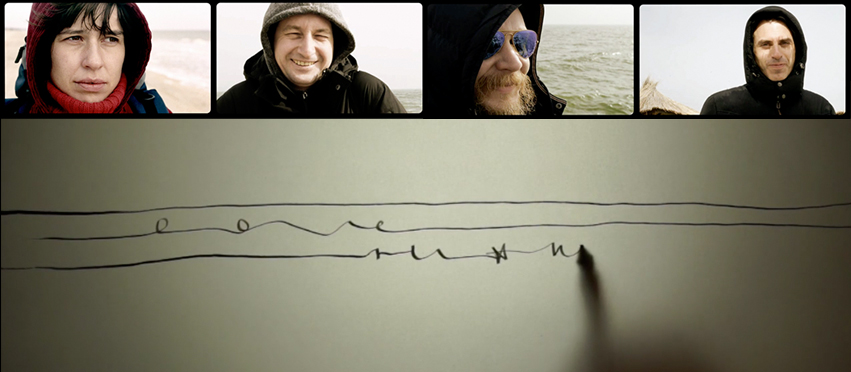

Автори проекту «роздІловІ», що поєднує поезію Сергія Жадана, музику Олексія Ворсоби та Влада Креймера, і візуальні образи Олі Михайлюк, представили англомовну версію однієї з композицій – The Simplest Words. У запрошенні на презентацію, що відбулася під час цьогорічного Форуму видавців, зазначалося: «Поезію важко перекласти, не втративши головного — ритму, інтонацій і пауз. Ми шукаємо нові способи роботи з текстом, використовуючи голос, музику та графіку, що разом допомагають долати мовні кордони». Враженнями від цієї спроби інтердисциплінарного перекладу ділиться науковець і музикант Бенджамін Коуп, для якого англійська мова є рідною. | The authors of rozdiLOVi project that combine poetry by Serhiy Zhadan, music by Alexey Vorsoba and Vlad Kreymer, and visual images by Olia Mukhailiuk presented the English version of one of the tracks – The Simplest Words. In the invitation to presentation that took place on The Lviv Publisher’s Forum they write: "Poetry is difficult to translate without losing the main features – rhythm, intonations, and pauses. We are looking for the new ways of work with text using voice, music, and graphics which together help to overcome language boundaries”. The native English speaker, scientist and musician Benjamin Cope shares his impressions from this effort of the interdisciplinary translation. |

«The Simplest Words»

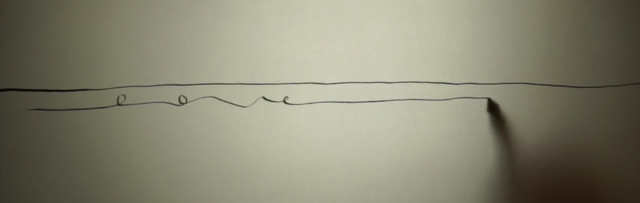

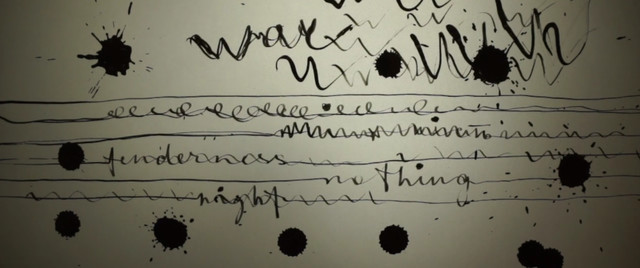

«Більше поезії Танцюй» Мій тато, 2016 Інструкція самому собі після смерті моєї мами, написана таким впізнаваним почерком в особистому записнику зі списком справ, який він тримає біля ліжка. Я побачив її вранці перед поверненням до Польщі. Як осягнути одну смерть в Бедфордширі (але «мою», моєї матері), знаючи про війну на сході України? «Слова, якими можна все пояснити» завжди прості, але пояснювальний потенціал мови посилюється — або порушується — електронними звуками загублених радіочастот, які потріскують над протяжними коливаннями акордеона, контрастом між написаними словами та акустичними властивостями голосу (ти просто ще один голос в її житті... можливо, найбільш різкий... можливо, найбільш виразний, або ж можливо, вона ставиться до нього, як до свого). Слова дрейфують між фокусом і розфокусом мальованих ліній, партитурою і розмитими звивинами вібруючих частот — прості, написані від руки різними мовами, постають з ліній і спадають в них назад. Комунікаційна функція мови відтіняється – або ускладнюється – почерком, малюнками. На противагу програмам, що алгоритмічно прогнозують використання слів, писання від руки знаходиться на перетині мови і хореографії життя. Свідомість і рука взаємодіють, проводячи лінії, що можуть збирати нас разом, а можуть розділяти: підписи є ознакою індивідуальної ідентичності, написаний від руки текст іноземцеві сприймати значно складніше, ніж друкований. Що більш промовисте, коли йдеться про прожиті життя: зміст чи матеріальність виведених рукою слів? | "More Poetry Dance” My Dad, 2016 Instructions to himself after my mum died, written in the handwriting that is so completely his own in the ‘things-to-do’ notepad that he keeps beside his bed, that I found on the morning before I returned to Poland. How to translate one death in Bedfordshire (but mine, my mum’s) in relation to a war in East Ukraine? "The simplest words” can explain it all, but this explanatory potential of language is reinforced, or compromised, by the electronic sound disturbance of a lost radio frequency crackling over the stretched vibrations of an accordion, by the contrast created between written words and the aural qualities of voices ("you were just another voice in her life” … "maybe the harshest” or "the clearest”, or one that "maybe she treats as your own”) and by the drifting in and out of focus of drawn lines, perhaps of a musical score or the blurred indentations of vibrating frequencies, with words, the simplest, hand-written in different languages rising from the lines and then descending back down into them. The communicational function of language is shadowed or obstructed by a hand writing, or drawing. Against the spread of programmes that algorithmically predict words to use, handwriting stands at the intersection of language and the choreography of living. Mind and arm act to draw lines that can bring us together and that also keep us separated: signatures are the mark of individual identity and different nations’ handwritings are much more difficult to ‘read’ for an outsider than typed script. Is it the content or the materiality of hand-traced words that speaks to us of lives lived? |

А можливо, ми бачимо не слова, а хвилі чи знаки ще незнаної каліграфії. Чи хвилясті лінії на електронному дисплеї в лікарні, що показують, продовжується життя чи ні. Не слова або музику, а образи війни — чи звуки в цій композиції наштовхують нас на таке «прочитання»? Ми бачимо слово «любов» чи кола (дірки, отвори) і хребти уздовж прокресленої лінії горизонту? Чи сходиться все це разом у літері «ж» слова «ніжність»? І чи «ніжність» — це те саме, що «tenderness» з її гострою «t», яка переходить у згасаючі вигини «s» «s», чи щось змінене або зрушене в процесі перекладу…? Чи товщина, кут і форма лінії відіграють вирішальну роль у передачі сенсу – як на мапі, чи значення твору — в рухах пера і руки, в медитації, яку переживає невидимий письменник/каліграф… Через різноманітність способів вираження, не зрозуміло, що вас (мене і тебе, нас, поезію, автора і «її», «націю», людство) тримає разом, окрім страху втратити один одного (в цей момент в музичному сценарії з’являється «нічого»).

Справді. Множина художніх прийомів дозволяє провести асоціативні паралелі з текстом, одягає невагомі слова в товщі досвіду, кидає виклик здатності слова промовляти (до нас, до мене, до тебе), перекладати досвід, з яким воно було народжене, на досвід мого (твого) життя. Вагання вірша дають час на трансформації, ритм твору робить рух видимим, і метаморфози, властиві іншим способам вираження (звук, музика лінія, образ), стають відчутнішими — додаючи словам того, що вони не можуть вловити. В той же час поезія вловлює це краще, ніж будь який інший спосіб мовлення, бо вона бореться з обмеженістю мови у здатності надавати моменту, що зараз минає, необхідного йому багатства, ясно виражаючи бачення тих, кому історія відмовила у праві говорити. Мовою, яку я можу чути, сприймати, розуміти. | Or perhaps what we see are not words, but waves, or the icons of an as yet unknown calligraphy, or bumps along the moving electronic displays that indicate in a hospital whether life goes on, or not: thus not words or music, but images of war (or is the sounds of the piece that suggest this ‘reading’). Do we see the word "love” or circles (holes, wholes) and ridges along a lined landscape? Or does it all come together in "ж”, the "zh” of ‘nezhnist’, and is "nezhnist” the same as "tenderness”, with its sharp "t” drifting into the diminuendoing furrows of "s” "s”, or is something lost or moved in the processes of translation…? Or is it here the thickness, angle and shapes of the lines that are crucial in transmitting meaning, as on a map, or is the meaning of the piece that of the movement of the pen, the arm and the meditation experienced by the unseen writer/calligrapher… Given the diversity of modes of expression, "Nobody knows what keeps you (me and you, us, the poem, the author and ‘her’, a ‘nation’, humanity) together” "except the fear of losing one another” (at which point "nothing” appears on the musical script).

Indeed. The plurality of artistic effects both draw out associative parallels with the words of the poem, clothing weightless words in the thickness of experience, but at the same time challenge the words’ ability to speak (to us, to me, to you), to translate the experience from which it was born into the experience of my (your) life. The hesitations of the poem allow time for transformations, the rhythm of the piece makes movement visible, and thus the metamorphoses inherent in the other modes of expression (sound, music, line, image) palpable – weighing the words down with what they cannot grasp. And yet, grasp better than any other mode of language – for poetry fights with the limits of language’s ability to express, to give the passing moment the richness that it demands, and to articulate the perspective of those whom history has denied the right to speak. In a language that I can hear, understand or accept. |

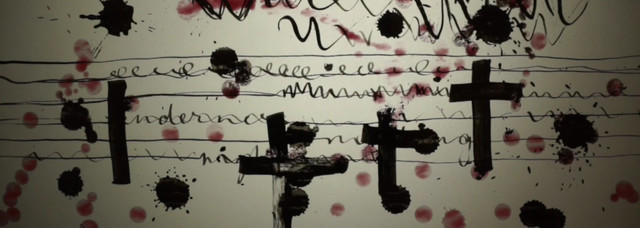

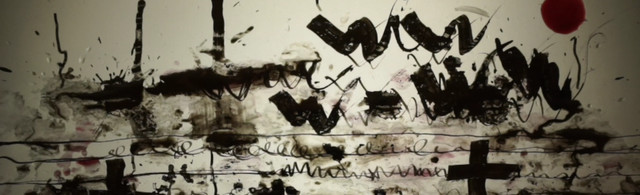

Потім знову ідуть знаки, звуки, елементи письма чи стирання: крапки «і» як свідчення того, що невагомий цей апарат тримається в повітрі, краплі елекронних сигналів чи самої невагомості, птахи чи «w» війни, що виростають над партитурою, нашаровані поверх слів слова, плями чорнила. Матеріальна сутність древніх або іншоцивілізаційних підходів до письма, яка ставить виклик нашому спрощеному розумінню комунікації. Вибухи, що залишають дірки у словах, ускладнюючи або повністю знищуючи їх здатність пояснювати навіть найпростіші речі. Цяткування вологими криваво-гранатовими плямами вносить колір у світ, який був хоч і багатовимірним, але чорно-білим. Поезія кидає виклик Богу, що супроводжується появою жорстких виразних хрестів, наростаючою інтенсивністю нерозбірливої розмови. З’являються руки, які гладять сплутані лінії, нашаровані слова і знаки. Розмиваючи, перемішуючи чи стираючи їх? Волога — сльози чи вода — посилює розмивання, уможливлює новий рух чорнила і знову виносить слово «війна» в ясний фокус уваги. Або ж, оскільки вірш, здається, досягнув свого темного апогею, волога стає зброєю гарпунника? | Then come further figures, sounds or elements of writing or erasure: "i’s” dots, or proof of floating, drips of apparatus sounds or of weightlessness, birds or the "w” of war rising over the score, words overwritten, blots of ink: the material essence of ancient and other civilisations’ approaches to writing that challenge our simplified sense of reading, or communication, or the blasts of explosions leaving holes in the words, handicapping or annihilating the ability to explain even the simplest things. The dotting of moist blood-pomegranate stains brings colour to a world that, although multidimensional, was black and white. The poem utters a challenge to God, and with it comes the imposition of severe thick crosses and the rising volume of an indecipherable conversation. Hands appear, massaging the conflicted lines, overwritten words and icons, blurring, remoulding them together or rubbing them out? Moisture, tears or water, adds to the blurring, making possible new movements of ink and bringing the word "war” into a renewed clarity of focus. Or just as the poem seems to reach a dark climax, does the moisture provide a medium for the harpooner? |

Бо хиткі намальовані лінії (сліди гарпунних пострілів?) починають рухатися вертикально через папір, разом із обіцянкою, що верес і чорна трава будуть квітнути. Вони посилюють відчуття деструктивного хаосу, або відкривають новий вимір, цю каліграфічну картографію наслідків війни. Тон загадково змінюється:

Через зім’яте паперове поле бою перед вашими очима у кінці вірша — arte povera зруйнованої землі, поезія, світ, любов і війна постають переплетеними в образі гарпунника, в якому віра в можливість спілкування, незважаючи на всі блок-пости і сумніви, у цвітіння вересу і чорної трави, в присвяти на першій сторінці резонує з тією вірою, що тримає тебе в сідлі навіть тоді, коли твої шанси такі малі, що від тебе нічого не хочуть навіть твої командири. | For wobbly drawn lines, (of trails of harpoon shots?), start to move vertically across the paper, along with the promise that the heather and the black grass (your eyes?), will flower, adding to the sense of destructive chaos or opening a new dimension, a sense of possibility, to this calligraphic cartography of the impact of war. The tone changes, but enigmatically: "Her voice will always be with you. A thank you and a dedication on the first page will always be for you. Carry them harpooner, like a weapon in your pocket…” Through the crumpled battlefield of paper in front of our eyes at the end of the poem, the arte povera of a broken land, poetry, the world, love and war emerge inter-tangled in the problematic image of the harpooner – in which faith in the act of communication despite all the check-points and hesitations, in the flowering of the heather and black grass, and in the dedication to you resonates with the faith which keeps you going after being abandoned by your commander. |

Поезія в «Словах, якими можна все пояснити...» постає підсиленою, але й атакованою з усіх боків тоном, голосом, звуками, музикою, лініями, кольором, рухом, паузами, формою, прогалинами, ваганнями, дотиком, а отже – глибоким проникненням за те, що я вважаю мовою, за межі мого розуміння. Поезія, свідома своїх недоліків, розгортається, перекладаючи досвід у щось поза змістом. Але не беззмістовне, скоріше має бути випущений гарпун, щоб захопити сенс нового досвіду. Відчайдушне прагнення вірити в життя, любов, війну і читання поезії. «Більше поезії Танцюй» | Poetry in "The Simplest Words…” emerges assisted and attacked on all sides by tone, voice, sound, music, lines, colour, movement, still, shapes, gaps, hesitations, massage, and thus a deep immersion of an experience beyond what I recognise as language, and beyond my understanding. Poetry, conscious of its lacks, reaches out, translating experience into somewhere beyond meaning. Not meaningless: rather the harpoon to be fired to capture experience as meaning. Leaps of faith in life, love, war and reading poetry. "More poetry Dance” |

| Бенджамін Коуп (Benjamin Cope) — доктор культурології, директор Лабораторії критичного урбанізму. Його наукові інтереси зосереджені на соціально-просторових змінах у Східній Європі з акцентом на культурних заходах і критичній картографії. У своїх дослідженнях є досить радикальним, тож переїхав з Британії безпосередньо у місце своїх наукових зацікавлень — до Польщі. Зараз живе у Варшаві, де працює у департаменті освіти Національної галереї мистецтв Zachęta, є культурним активістом Асоціації «Stowarzyszenie My». Цікавиться можливостями інердисциплінарного перекладу, і тому задіяний у багатьох проектах, що сполучають музику, візуальне мистецтво, театр, і акціях у публічних просторах. | Benjamin Cope – Ph.D, director of the Laboratory of Critical Urbanism. His scientific interests focus on socio-spatial change in the Eastern Europe, with a particular accent on cultural events and critical cartography. He is quite radical in his research, thus moved from the UK directly to the place of his interests – Poland. Now Benjamin lives in Warsaw, where works in the Education Department at Zachęta National Gallery of Art, as a cultural activist in the Association "Stowarzyszenie My”. He is interested in the interdisciplinary translation, thus takes part in the various projects combining music, visual art, theatre, and in the interventions in public spaces. |

Українську версію композиції можна прослухати тут soundcloud.com/rozdlov-slova